I’m a dual citizen of Australia and the allegedly United Kingdom. However, for the time being I’m back in Melbourne with my young family after over a decade in London, and I’m returning to the idea that I am, for better or worse and wherever I reside, an Australian playwright. This is where I was born and became established as a writer. I learned an incredible amount being – and remaining, I hope – in London’s industry, but wandering around what is now my local park has got me thinking about how our environments might shape our attitudes to the most basic of things without our consciously knowing it.

For I have to say, some plays that fly for audiences in Australia seem to be impenetrable for audiences in the UK. In my time reading for UK theatre companies, I listened to other readers express their incomprehension at some writing from Australia that I loved (and knew that others in Australia also valued). There’s a book by the drama critic most important to the New Wave of 1970s Australian drama, Katharine Brisbane, that goes by the name, Not Wrong Just Different, the title taken from one of her reviews where she celebrated a newly-emerging and self-conscious difference in Australian drama. What contributes to this difference?

And, so, my tiny hypothesis is to do with trees.

That’s right. Trees. But why?

Most drama teachers will point to the importance of structure – even in opposition to it. Structure often gets expressed as being like a tree. What’s considered a great play could be compared to a grand tree, such as an oak or a cedar or a weeping willow. Substitute premise/argument for trunk, acts/scenes for branches with the roots of specific backstory and the foliage being the words and action.

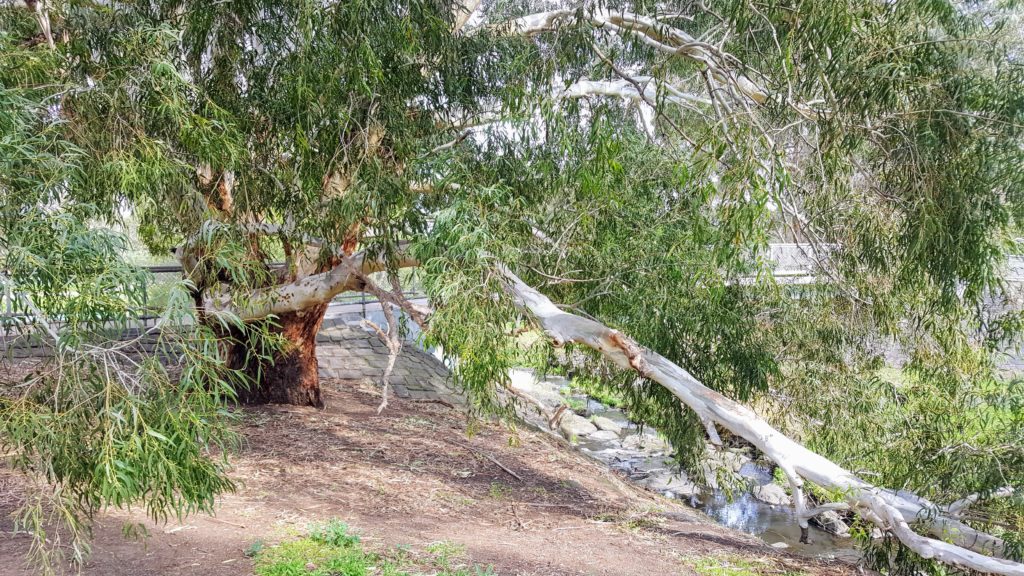

Australia being a country invaded by Europeans, the Europeans planted a few of their trees to feel more at home. Such as the weeping willow in my neighbourhood park. The structure of it appears to be the thing off which everything else hangs. In dramatic terms, the thrust of the play carries all else along with it.

But the trees that dominate the landscape of where most inhabitants of this continent live look wildly dissimilar. While away, these trees that I missed most were Australia’s ubiquitous eucalyptus, or ‘gum’ trees. But what makes a gum a gum?

What draws animals and insects to, and defines, the gum tree is the breakage of its bark, which releases sap, the ‘gum’ to which the name refers. This changes the very way the tree appears and has evolved and structures itself. To look for the structure of a gum tree from, say, the European perspective is to miss the point.

Might it be that Australian drama that meets the structural expectations of its audiences is about the surfaces breaking upon its base rather than deep roots resulting in appearance? Think of how the plays of Dorothy Hewitt, Katherine Susannah Pritchard, Mona Brand and Patrick White work, or are claimed not to work.

This is not to say that structure isn’t necessary for Australian playwrights. It’s just a thought that maybe, just maybe, because of our lived environment that structure serves difference purposes. Gum trees bend and grow and can be as majestic as any European tree, but their beauty lies in the breaking of the bark. From the snap, the sap, along with twists improbable to those unfamiliar.

But what do I know? My heart is in two places.